Redefining Engagement: How Baltimore City Public Schools Transformed its Approach to Adopting Instructional Materials

Read one district's story about the power and lasting impact that comes with involving educators and the community at every step of the materials selection process.

2019/12/02

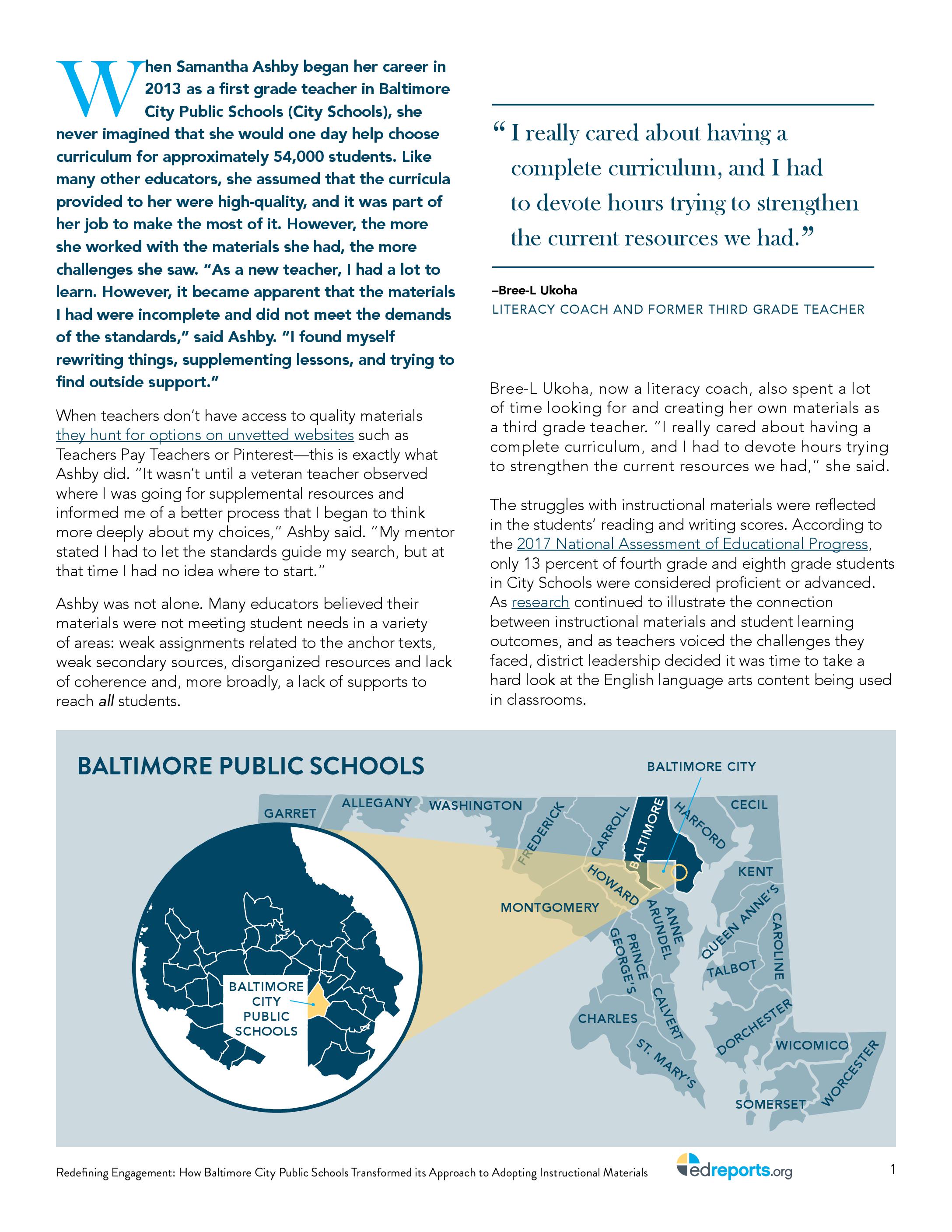

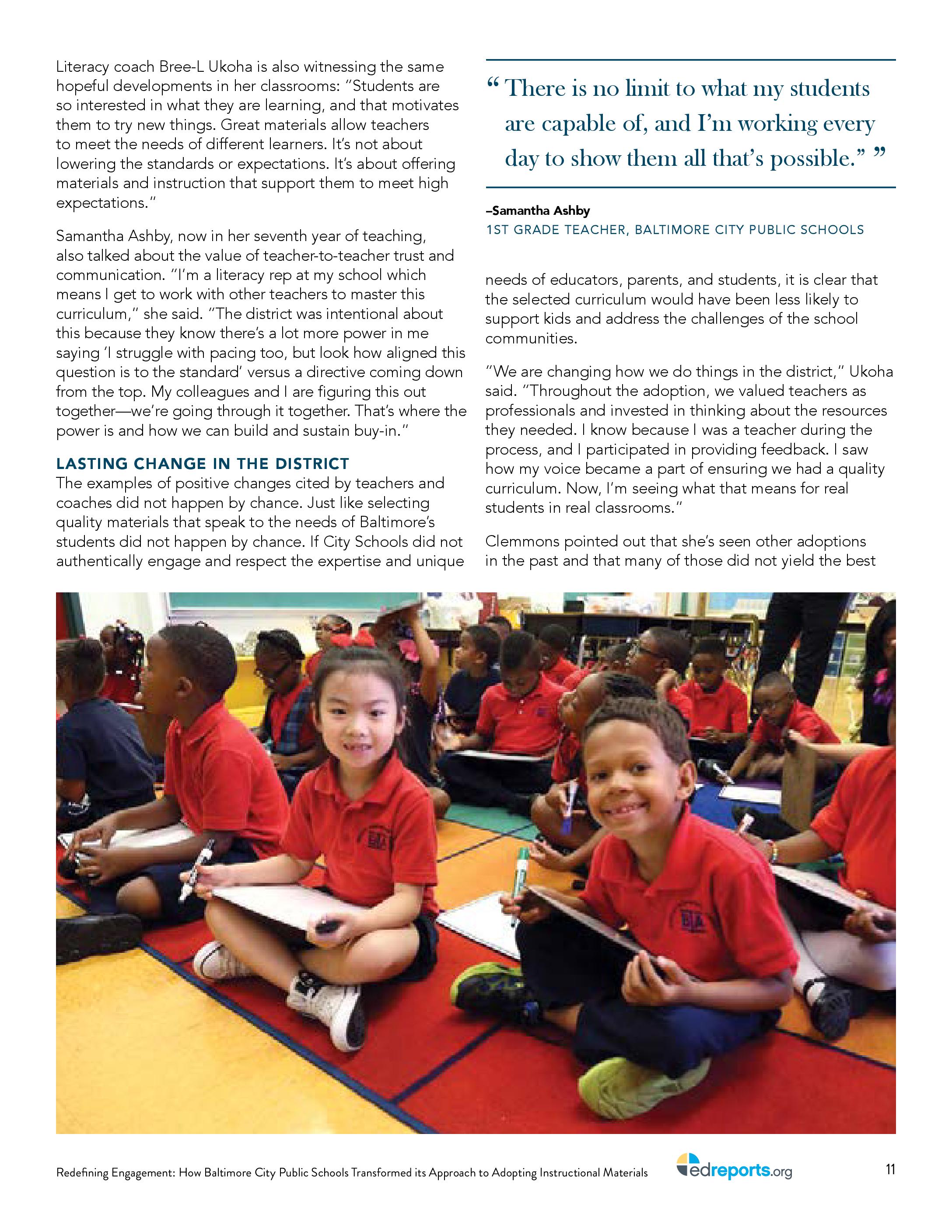

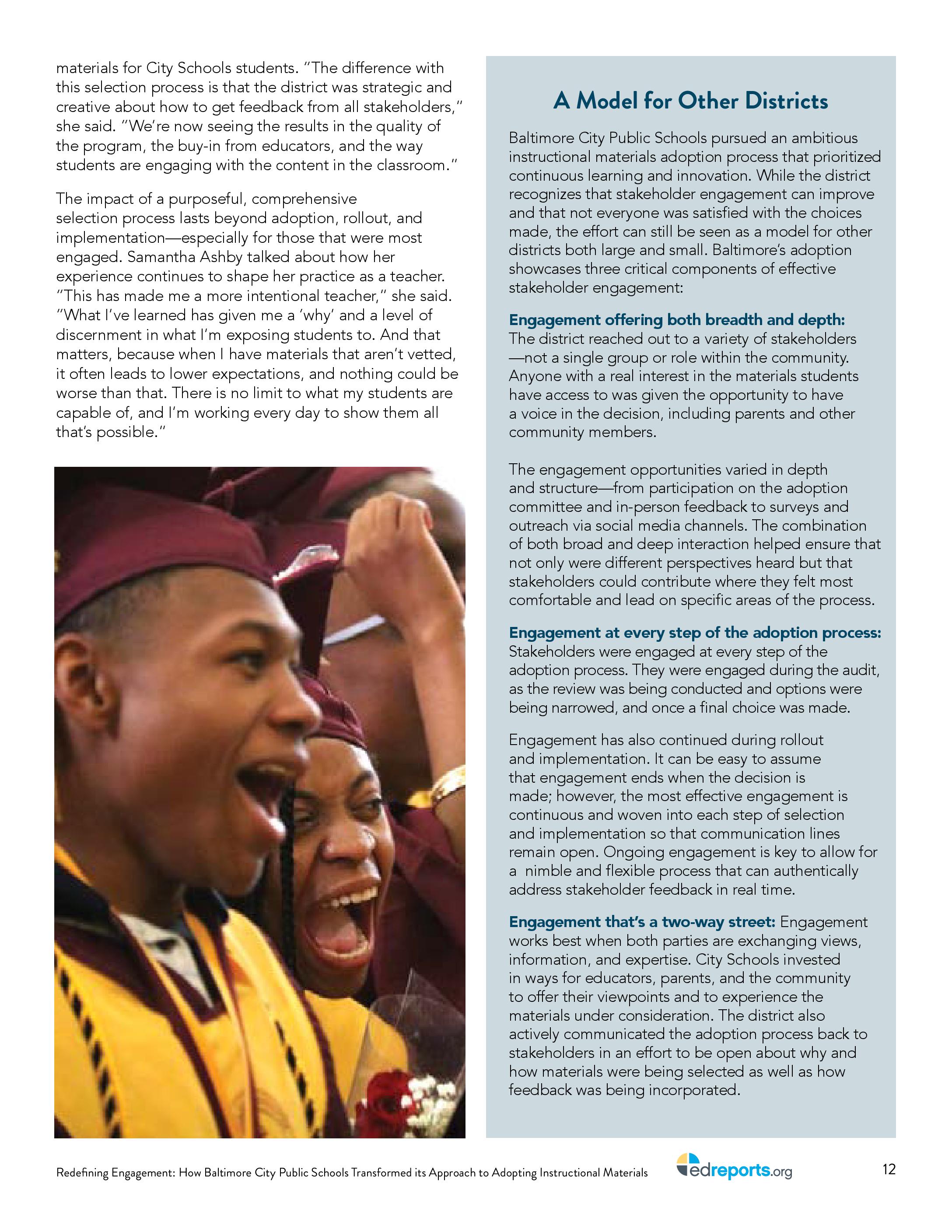

When Samantha Ashby began her career in 2013 as a first grade teacher in Baltimore City Public Schools (City Schools), she never imagined that she would one day help choose curriculum for approximately 54,000 students. Like many other educators, she assumed that the curricula provided to her were high-quality, and it was part of her job to make the most of it.

However, the more she worked with the materials she had, the more challenges she saw. “As a new teacher, I had a lot to learn. But it became apparent that the materials I had were incomplete and did not meet the demands of the standards,” said Ashby. “I found myself rewriting things, supplementing lessons, and trying to find outside support.”

When teachers don’t have access to quality materials they hunt for options on unvetted websites such as Teachers Pay Teachers or Pinterest—this is exactly what Ashby did. “It wasn’t until a veteran teacher observed where I was going for supplemental resources and informed me of a better process that I began to think more deeply about my choices,” Ashby said. “My mentor stated I had to let the standards guide my search, but at that time I had no idea where to start.”

Ashby was not alone. Many educators believed their materials were not meeting student needs in a variety of areas: weak assignments related to the anchor texts, weak secondary sources, disorganized resources and lack of coherence and, more broadly, a lack of supports to reach all students.

Bree-L Ukoha, now a literacy coach, also spent a lot of time looking for and creating her own materials as a third grade teacher. “I really cared about having a complete curriculum, and I had to devote hours trying to strengthen the current resources we had,” she said.

The struggles with instructional materials were reflected in the students’ reading and writing scores. According to the 2017 National Assessment of Educational Progress, only 13 percent of fourth grade and eighth grade students in City Schools were considered proficient or advanced.

As research continued to illustrate the connection between instructional materials and student learning outcomes, and as teachers voiced the challenges they faced, district leadership decided it was time to take a hard look at the English language arts content being used in classrooms.

Read what happened next and learn more about Baltimore City's ELA adoption including how the district engaged teachers and the community to choose an aligned program that would truly meet students needs.

Related Resources